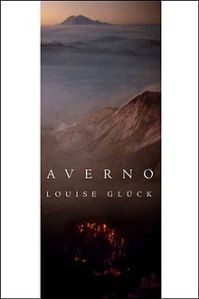

Nell’occasione dell’assegnazione del Premio Nobel per la Letteratura 2020 a Louise Glück riproponiamo le traduzioni di Anna Maria Curci e Gianni Montieri di tre poesie tratte dalla raccolta Averno del 2006.

The Night Migrations

This is the moment when you see again

the red berries of the mountain ash

and in the dark sky

the birds’ night migrations.

It grieves me to think

the dead won’t see them–

these things we depend on,

they disappear.

What will the soul do for solace then?

I tell myself maybe it won’t need

these pleasures anymore;

maybe just not being is simply enough,

hard as that is to imagine.

Le migrazioni notturne

Questo è il momento in cui rivedi

le bacche rosse del sorbo selvatico

e nel cielo scuro

le migrazioni notturne degli uccelli.

Mi addolora pensare

che i morti non le vedranno –

queste cose dalle quali dipendiamo

scompaiono.

Che cosa farà l’anima allora per trovar conforto?

Mi dico che forse non avrà più bisogno

di questi piaceri;

forse non essere, e nient’altro, basta, semplicemente,

per quanto sia arduo immaginarlo.

(traduzione di Anna Maria Curci e Gianni Montieri)

Crater Lake

There was a war between good and evil.

We decided to call the body good.

That made death evil.

It turned the soul

against death completely.

Like a foot soldier wanting

to serve a great warrior, the soul

wanted to side with the body.

It turned against the dark,

against the forms of death

it recognized.

Where does the voice come from

that says suppose the war

is evil, that says

suppose the body did this to us,

made us afraid of love–

Lago craterico

C’è stata una guerra tra il bene e il male.

Abbiamo deciso di chiamare il corpo il bene.

Questo ha reso la morte il male.

Ha fatto ribellare l’anima

contro la morte, completamente.

Come un fante che vuole

servire un grande guerriero, l’anima

ha voluto schierarsi con il corpo.

Sì è ribellata contro il buio,

contro le forme di morte

che riconosceva.

Da dove arriva la voce

che dice supponi che la guerra

sia il male, che dice

supponi che sia stato il corpo a farci questo,

ci abbia resi timorosi dell’amore –

The Evening Star

Tonight, for the first time in many years,

there appeared to me again

a vision of the earth’s splendor:

in the evening sky

the first star seemed

to increase in brilliance

as the earth darkened

until at last it could grow no darker.

And the light, which was the light of death,

seemed to restore to earth

its power to console. There were

no other stars. Only the one

whose name I knew

as in my other life I did her

injury: Venus,

star of the early evening,

to you I dedicate

my vision, since on this blank surface

you have cast enough light

to make my thought

visible again.

La stella della sera

Stasera, per la prima volta in molti anni,

mi è apparsa nuovamente

una visione dello splendore della terra

nel cielo vespertino

la prima stella sembrava

crescere in fulgore

man mano che la terra si oscurava

fino a non poter diventare infine più buia ancora.

E la luce, ch’era la luce della morte,

pareva restituire alla terra

il suo potere consolatorio. Non c’erano

altre stelle. Solo quella

di cui conoscevo il nome

come nell’altra mia vita le recai

offesa: Venere,

stella del vespro,

a te dedico

la mia visione, ché su questo suolo spento

hai gettato quanta luce basta

a rendere il mio pensiero

visibile di nuovo.

Louise Glück, Averno, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006

(traduzione di Anna Maria Curci)

2 risposte a “Louise Glück, Premio Nobel per la Letteratura 2020. Rileggere tre poesie da “Averno””

L’ha ripubblicato su Paolo Ottaviani's Weblog.

"Mi piace"Piace a 1 persona

Ecco anche un mio contributo:

The Past

Small light in the sky appearing

suddenly between

two pine boughs, their fine needles

now etched onto the radiant surface

and above this

high, feathery heaven—

Smell the air. That is the smell of the white pine,

most intense when the wind blows through it

and the sound it makes equally strange,

like the sound of the wind in a movie—

Shadows moving. The ropes

making the sound they make. What you hear now

will be the sound of the nightingale, Chordata,

the male bird courting the female—

The ropes shift. The hammock

sways in the wind, tied

firmly between two pine trees.

Smell the air. That is the smell of the white pine.

It is my mother’s voice you hear

or is it only the sound the trees make

when the air passes through them

because what sound would it make,

passing through nothing?

Louise Glück

Il passato

Una lama di luce sottile appare nel cielo

improvvisa fra

due rami di pino i cui aghi sottili

s’incidono nella radiata superficie

e su nell’alto

cielo piumato –

Odora l’aria. È l’odore del pino strobo,

più intenso se il vento gli soffia fra i rami

e il suono che fa è altrettanto strano,

eguaglia quello del vento in un film –

Ombre agitate. Le corde

danno il loro suono abituale.

Quello che odi adesso

sarà forse il canto dell’usignolo, i Vertebrati,

il canto del maschio che corteggia la femmina –

Le corde scorrono. L’amaca

oscilla al vento, legata

stretta tra due tronchi di pino.

Odora l’aria. Questo è l’odore del pino strobo.

È la voce di mia madre quella che odi

o è solo il suono che fanno gli alberi

quando l’aria li va frugando

perché poi che suono farebbe,

l’aria, se frugasse nel nulla?

(Trad. N. Muzzi)

"Mi piace""Mi piace"